Introduction

Background.

In 1999, the Connecticut Freedom of Information

(FOI) Commission and the Connecticut Foundation for Open Government, Inc.

(CFOG) co-sponsored a survey of compliance by local agencies with the state FOI

Act. The results of that survey were

truly abysmal as reported and published that year in Access to Public Records:

A Survey of Compliance by Local Agencies with the Freedom of Information Act.

Over

the last several years, there have been a number of surveys dealing with local

compliance with FOI laws. But to our

knowledge, none of these surveys addressed FOI compliance by state

agencies.

As in the case of

our 1999 local agency survey report, we enlisted Harry Hammitt, editor and

publisher of Access Reports, and

author of the Report of the National Privacy and Public Policy Symposium, to

provide an independent analysis of the state agency survey. We were also

fortunate to enlist the assistance of Professor Jerry Dunklee of Southern

Connecticut State University who provided students from his 2001 Winter Term

journalism course on Law and Ethics to act as surveyors.

Concept

of the Survey.

Based

upon our experience with the 1999 survey, we knew that we had to set certain

limitations. The principal limitations

were (1) choice of agencies to be surveyed, (2) choice of the test for

compliance, and (3) choice of survey protocol.

The time period during which the survey would have to be completed also

had to be limited to prevent agencies from becoming aware that they were the

subject of a survey rather than merely responding to individual requests for

information. We have no information to

believe that the survey, essentially conducted over a two to three day period

in March of 2001, was compromised in this, or any other, way.

In

light of these limitations, it is important to note that this survey was

conceived to produce a snapshot of compliance with the FOI Act. If other records or agencies were chosen,

different results might have been achieved.

Those results might have been better or worse than those achieved in

this survey. But for all the reasons

explained in this report, we believe that the snapshot produced by this

survey presents a fair view of the state of compliance with FOI laws by

Connecticut state agencies.

Agencies

Surveyed.

We

originally hoped to survey every state executive branch agency. We could not accomplish this for several

reasons. First there is no one

comprehensive list of such agencies. We

acquired lists of state agencies from several sources, including the state Department

of Administrative Services, the Office of Policy and Management, the Governors

Office, the Office of Fiscal Analysis and the Office of Legislative

Research. Some agencies on these lists

we simply could not physically locate.

Others appeared to us to have gone out of business. Still others had no staff or office. When we filtered out these agencies, we had

created a list of about 100 agencies.

As we further

analyzed the remaining agencies on our list, we noted that many licensing

boards and commissions did not have their own staff, but were serviced by the

same personnel from larger agencies, particularly the Department of Consumer

Affairs with respect to boards and commissions having jurisdiction over trades

people, and the Department of Public Health with respect to boards and

commissions having jurisdiction over the health professions. Obviously for the purposes of this study it

made no sense to survey the same agency personnel for more than one agency

because presumably we would get the same results for all the agencies about

which we inquired; and furthermore the agency personnel were more likely to

view the request for records as a test rather than an individual citizens

request for public records.

Finally, there are a

total of four state universities under the state university system (not

including the University of Connecticut which has its own governance) and eight

state community-technical colleges under their own system. Because we thought that the governing system

for each set of universities and colleges would be controlled by the same set

of policies -- and perhaps the same personnel -- we decided to survey only two

state universities, four community-technical colleges and the University of

Connecticut at Storrs.

In all, a total of

72 state agencies were supposed to be surveyed. In two cases (Gateway Community-Technical College and Norwalk

Community-Technical College), however, the assigned surveyor failed to conduct

the survey. And unfortunately, the

survey results were lost and could not be re-created in another two cases

(Department of Education and the Office of the Secretary of the State). Because of the surveys design, these

agencies could not be re-surveyed when we learned of these missing reports.

From our own

experience, we knew that it was likely that building security would prevent

some surveyors from reaching their assigned agencies without violating certain

provisions of the FOI Act. For this

reason, we divided the survey questionnaire into two parts. The first part addresses compliance with the

FOI Act by building security personnel.

These individuals are usually engaged by the agency in charge of the

building in which one or more state agencies are located (in most, if not all

cases, the state Department of Public Works).

The second part of the questionnaire addresses compliance with the FOI

Act by personnel of the surveyed agency.

In three cases (Department of Information Technology, Department of

Mental Retardation and Department of Transportation), the surveyors were not

permitted by building security to visit the assigned agencies. In those instances, we validated the survey

results only with respect to the first part of the questionnaire.

In another six

instances (Attorney General, Board of Examiners for Nursing, Division of

Criminal Justice, Governor, Lieutenant Governor and Treasurer), the surveyors

were told that there were no records responsive to the request. The offices of Attorney General, the Chief

States Attorney (Division of Criminal Justice), Governor, Lieutenant Governor

and Treasurer stated that because these officials were constitutional

officers, they did not have to document their time or attendance. A receptionist in the office of the Board of

Examiners for Nursing stated that the members of the board were all volunteers

and there were no senior officials of the agency for whom attendance records

were kept. We accepted this explanation

on its face and consequently we validated the survey results in these cases

only with respect to the first part of the questionnaire.

Thus, of the 68

state agencies for which we received survey results, 59 were validated for the

entire survey. An additional nine

agencies were validated only with respect to the first part of the

questionnaire dealing with access to the building in which those agencies are

located.

Test

for Compliance.

Great

care was taken in designing the survey.

The test for compliance could not be overly complicated to administer or

unfairly technical in its requirements.

For these reasons, we chose to focus on the open records provisions of

the FOI Act rather than its open meetings provisions.

Section

1-210(a) of the Connecticut General Statutes, the centerpiece of the FOI Act (Hartford v. FOI Commission, 201 Conn.

421 at 429-430 (1986)), in pertinent part reads:

Except as otherwise provided by

any federal law or state statute, all records maintained or kept on file by any

public agency, whether or not such records are required by any law or by any

rule or regulation, shall be public records and every person shall have the

right to inspect such records promptly during regular office or business hours

or to receive a copy of such records in accordance with the provisions of

section 1-212.

Section 1-212(a) of the Connecticut General

Statutes, in turn, provides in relevant part:

Any person applying in

writing shall receive, promptly upon request, a plain or certified copy of any

public record. The fee for any copy

provided in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act [shall be as

follows]. . . .

Several

key points are clear from these statutes.

First, unless exempt by federal law or state statute, every person has

the right to inspect any record kept by

a public agency promptly, without charge and without putting the request in

writing. Second, there are no statutory

preconditions to access to inspect public records. Thus, a person need not identify oneself before inspecting

nonexempt public records, nor need he or she justify the request by giving a

reason for seeking the information.

In testing how well

or how poorly the FOI Act is working for the average citizen, we believe that

it was crucial not only to look at whether or not inspection was granted, but

also whether public agencies were placing impermissible conditions on the right

to inspect. So we asked the surveyors

to record whether there were any preconditions to their entering the building

in which the agency to be surveyed is located.

Such preconditions included whether there was a requirement that they

give their names, identify whom they were going to see or provide

identification.

In addition, we

asked the surveyors to record whether each agency demanded a fee for inspection

and whether it demanded that the request be put in writing. We also asked the surveyors to report on

whether agency employees asked them to identify themselves or to provide the

reason they wanted to see the requested records. And we asked them to report on the promptness in complying with

their requests and on the degree of cooperation they experienced in each

transaction. Because the choice of

yes or no, or a scale of cooperation, does not necessarily reflect the

reality of every situation presented, we asked the surveyors to enter comments

(both positive and negative) which they thought would help clarify their

responses in light of the experiences they encountered.

Moreover, the law in

Connecticut is that when a public record contains both exempt and nonexempt

information, the agency must disclose the nonexempt information. Kozlowski

v. FOI Commission, 1997 WL 435860 (Super. Ct. CV 960556965, Maloney,

J.). Accordingly, we asked the

surveyors to record whether each agency would only permit inspection if certain

information were redacted or masked.

In

choosing the records we had the surveyors request, great care was also

taken. We tried not to be unfairly

technical or onerous. We tried to pick

records that the agencies concerned knew, or should have known, were

public. The FOI Commission was prepared

to provide the appropriate citation to the applicable law if any agency

contacted us. To our knowledge,

however, only one agency contacted the commission (the Office of the Secretary

of the State), and that appears to have occurred after responding to the

survey.

In

our 1999 survey of local agencies, we selected one specific kind of record for

each of three categories of agencies (i.e., municipal clerks, police

departments and superintendents of schools).

We were then able to tabulate and compare results within each category

of agency as well as among all categories.

Because each state agency essentially has a different mission

from that of every other one -- and therefore generally maintains different

kinds of records -- we could only compare survey results among all state

agencies using records kept by all of them.

Consequently our choice of records for purposes of this survey were

limited to administrative records.

Because administrative records are typically maintained by a single unit

or group of employees in each agency, we decided to seek access to only one

particular kind of record.

For this survey, we

chose the attendance records of the agency head or the agencys highest ranking

paid employee, if the agency head was not a paid employee of the state. We defined Attendance Record to mean any

document that contains:

1.

The name of the person whose information the surveyor is seeking;

2.

The exact days and number of hours each day during the month of February

2001 during which the person whose information the surveyor is seeking was

recorded by the agency as having been present for work; and

3.

The precise days and number of hours during the month of February 2001

during which the person whose information the surveyor is seeking was recorded

by the agency as having been charged with sick leave, vacation leave, personal

leave or any other form of leave or absence, whether compensated or not.

The

information requested was specifically ruled to be public by the Connecticut

Supreme Court in the case of Perkins v.

FOI Commission, 228 Conn. 158, 177 (1993).

As stated in that case,:

The public has a right to know not

only who their public employees are, but also when their public employees are

and are not performing their duties. We

conclude that a records request under the . . . [FOI Act] for disclosure of the

numerical data concerning an employees attendance records, including or

limited to sick leave, does not constitute an invasion of personal privacy

within the meaning of . . . [§1-210(b)(2)]. Disclosure in this instance is required.

This decision

received a great deal of publicity and was the subject of much discussion by

public agencies in Connecticut because

it was the first time our state Supreme Court categorically defined the right

of personal privacy for purposes of the FOI Act. Thus, we believe that all state agencies knew, or should have

known, about this ruling and that the records requested must be provided.

Survey

Protocol.

The

survey protocol was quite simple. We

spent one class of over an hour training the surveyors. We asked the surveyors to act politely and

in a non-threatening, non-aggressive manner.

As stated earlier, we wanted to see how well or how poorly the FOI Act

is working for the average citizen who seeks access to, in this case, state

agency records. So we told our

surveyors neither to say that they were making their request pursuant to the

FOI Act or any other law, nor to demand to speak to a supervisor if they were

denied access. We also told them not to

threaten legal action of any kind, including an appeal to the FOI

Commission. We wanted the individuals

with whom the surveyors dealt to believe that there would be no consequences if

they denied access to the requested records.

A copy of the survey form is included in this report on pages 7 and 8.

If

the surveyors were asked to identify themselves or to give the reason that they

wanted to see the requested records, they were instructed to reply that they

would rather not say. If pressed to do

so in order to gain access to the records sought, they were told that they

either did not have to answer or could reply that it was part of a class

assignment, as long as they did not reveal it was for purposes of a

survey. They were informed that the

insistence upon their providing their names or the reason for their request as

a precondition to disclosure constituted a violation of the law. They were also told that although not

required, if they wanted to give their names, they were free to do so in order

to determine whether they would be given access to the requested records. In this regard, we also asked the surveyors

to look at any records provided so that it would appear they were actually

interested in them, thereby disguising that the request was for survey purposes

only. We explained that we had no

interest in what was in the records themselves, as long as the records appeared

complete and were responsive to the request made.

Most

of the surveyors were of traditional college age. But not all. We decided

that age, like race or gender, was not relevant to this survey. Since we were not testing compliance on the

basis of these factors, it did not matter who the surveyors were. They were simply people who, like everyone

else, were entitled to the records they sought promptly, and who, like everyone

else, were entitled to be treated with courtesy and civility. We did, however, ask the student surveyors

to dress neatly and not to wear college tee shirts, sweatshirts or caps or to

carry notebooks or anything else that would identify them as college students,

lest the officials have reason to speculate that a school project was the

reason for the request.

The

surveyors were instructed to complete the questionnaire for each agency

immediately upon leaving the premises.

They were told to write down the time and date of the visit, as well as

the address of each office visited, if different from the address provided, and

the names of the persons with whom they dealt.

We also asked the surveyors to write their comments at that time rather

than later when their recollection might not be as precise.

Obviously,

with a survey of this magnitude, not all surveyors followed these protocols to

perfection. But by and large most

performed satisfactorily and we believe the responses to the questionnaires are

accurate and valid. The patterns in the

survey responses support this conclusion.

We also met with the surveyors after they completed their work to

debrief them orally. This session

likewise confirmed to us the validity of the survey results as reported on the

completed survey questionnaires.

Format

and Purpose of Report.

The

remainder of this report consists of three parts. First is an analysis of the survey results in general. Second is an analysis of the survey results

alphabetically by agency. And finally,

there is a presentation of the conclusions reached by Mr. Hammitt with respect

to this survey.

Thanks

to CFOG, this report will be widely circulated within Connecticut. Each state agency head will receive a

copy. It will also be available through

the Connecticut library system and will be posted on the FOI Commissions

website (www.state.ct.us/foi) and

CFOGs website (www.ctopengovt.org). In this way, we hope that the report will

engender the great interest and discussion it deserves.

It is, of course,

easy to criticize the bearer of bad news, as the results of this survey well

may be perceived by many. Criticism is

therefore to be expected to one degree or another. That is why we have gone to some length to describe not only the

survey itself, but the law, reasons and thought that went into it. That is also why we have sought an

independent analysis of the survey results.

Nevertheless, we

hope that those agencies that were the subject of this survey, as well as those

that were not, will think about what this survey reveals and how to correct the

problems that have been exposed, particularly with respect to training their

employees who deal with the public in responding to FOI requests. Likewise, we hope that public policy makers

in Connecticut will use the survey and this report to determine whether changes

to the law ought to be made. After all,

the old adage that sunlight is the best disinfectant is as true literally as it

is metaphorically with respect to the harmful matters that can fester in the

murky recesses of unnecessary government secrecy. In large measure, the purpose of this survey and report has been

to direct the sunlight into some of these hidden recesses.

2001 STATE AGENCY SURVEY

AGENCY NAME

AND ADDRESS:

______________________________________________________

REQUEST TO INSPECT THE

ATTENDANCE RECORD OF

______________________________________________________

FOR THE MONTH OF FEBRUARY 2001.

**PLEASE

COMPLETE THE ENTIRE SURVEY, PLACING A CHECK MARK IN THE APPROPRIATE BOX AND

PRINTING WRITTEN RESPONSES LEGIBLY.**

1. Upon entering the building, were you asked

to:

a. Give your

name? Orally Y

ڤ N ڤ In

writing Y ڤ N ڤ

b. Identify

whom you were going to see? Orally Y

ڤ N ڤ In

writing Y ڤ N ڤ

c. Provide

identification? Y ڤ N

ڤ

2. After admittance to the building and finding

the correct office:

a. Were you

permitted to inspect the requested records? Y ڤ N ڤ

b. If you

were permitted to inspect the records, how long did you have to wait to see the

records? __________________

c. If you

were permitted to inspect the records, was any requested information omitted?

(e.g. blocked

out or portions missing) Y

ڤ N ڤ

If yes, what?

______________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________

d. If you

were NOT permitted to inspect the records, what was the reason given, if

any?

______________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________

e. Were you

asked to identify yourself? Y ڤ N ڤ

f. Were you

asked a reason for your request? Y ڤ N ڤ

g. Were you

required to provide a prepared written request? Y ڤ N

ڤ

h. Was there

a fee to inspect the records? Y ڤ N ڤ

3. How cooperative were the people you spoke

with? (Check the appropriate box). Reminder: This is not a rating of whether or not you

were permitted to inspect the records requested, it is simply a rating of the

amount of cooperation you received from the agency.

|

ڤ Very

Uncooperative

|

ڤ Somewhat

Uncooperative

|

ڤ Somewhat

Cooperative

|

ڤ Very

Cooperative

|

Please

explain your choice. _____________________________________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. Additional comments about survey (use reverse

side of this form if necessary):

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. Date of Survey: _________

Time Arrived at Agency Office: ____ Time Departed Agency Office: _________

Name

and title of person(s) with whom you dealt (ask politely, please).

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

**SEE THE REVERSE SIDE FOR

REQUIRED CERTIFICATION AND FOR THE DEFINITION OF ATTENDANCE RECORD.**

TO ASSURE PAYMENT AND REIMBURSEMENT, PLEASE LEGIBLY

COMPLETE AND SIGN THE FOLLOWING CERTIFICATION.

I certify that the information contained on this survey form is complete and

accurate to the best of my knowledge and that I conducted this survey on the

date indicated above.

______________________________

Signature

PLEASE PRINT LEGIBLY

Full Name:

____________________________________________________________________

Address (where

check should be mailed): ____________________________________________

Telephone

Number (during business hours):

__________________________________________

Professors

Name: _______________________________________________________________

ATTENDANCE

RECORD

For purposes of this

survey, the term Attendance Record means any document that contains:

1. The name

of the person whose information you are seeking (the title of the persons

office appears on the heading of this survey form);

2. The exact

days and number of hours each day during the month of February 2001 (e.g.,

February 1, 8 hours; February 2, 6 hours) during which the person whose

information you are seeking was recorded by the agency as having been present

for work; AND

3. The precise

days and number of hours during the month of February 2001 during which the

person whose information you were seeking was recorded by the agency as having

been charged with sick leave, vacation leave, personal leave or any other form

of leave or absence, whether compensated or not.

ADDITIONAL

COMMENTS

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Analysis

Introduction

After the

dismal results of the survey of local government agencies sponsored by the

Connecticut Foundation for Open Government and the Connecticut Freedom of Information

Commission in 1999, these organizations decided to follow up with a second

survey that would test compliance in state agencies. The results are now in and they are no better, and perhaps worse,

than those of local government agencies.

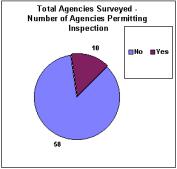

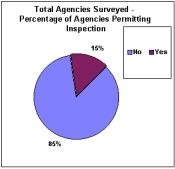

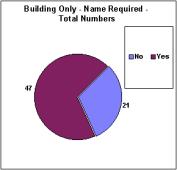

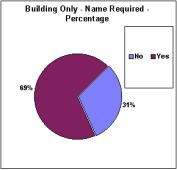

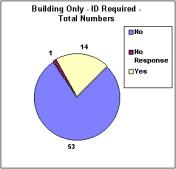

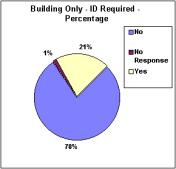

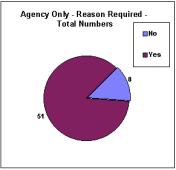

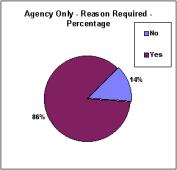

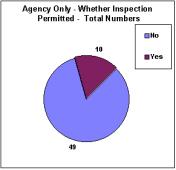

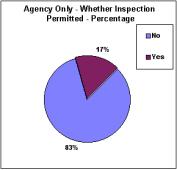

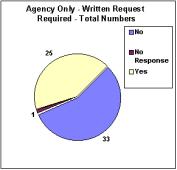

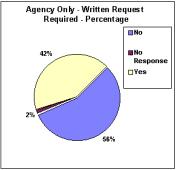

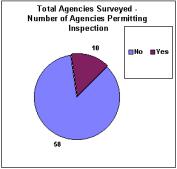

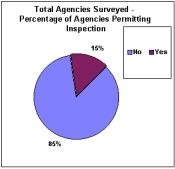

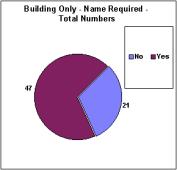

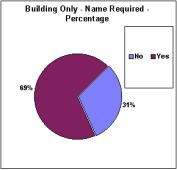

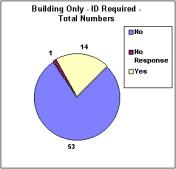

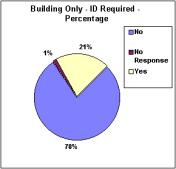

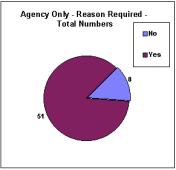

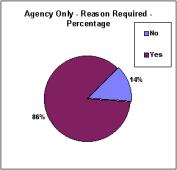

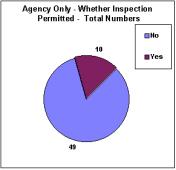

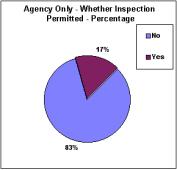

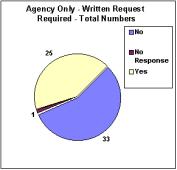

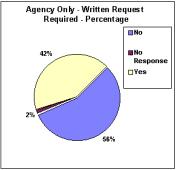

Of 68 state agencies surveyed, only 10, 15 percent (see Graphs 1 and 2),

allowed the surveyor to view the attendance record of the head of the agency

and only a single agency the Department of Banking was in complete

compliance with the standards developed for the survey.*

Graph

1 Graph 2

The statistical results speak

for themselves, but the comments of many of the surveyors all journalism

students of various ages at Southern Connecticut State University add an

extra layer of color, revealing frequent ignorance of the requirements of the

Freedom of Information Act and running the gamut from ignorance and

indifference to the use of force and threats.

There

are at least three different issues that arise from the survey. The first is the consistently poor

performance of agencies as a whole.

Beyond that is the conflict between allowing access to public records

and maintaining building security. Finally,

what, unfortunately, comes through all too clearly in the surveyors comments

is their personal disenchantment with government, their disappointment at the

frequent brow beating and wide-eyed stares they received at agencies when they

attempted to assert what, under the FOI Act, are clear statutory rights of

access to the requested records.

Agency Performance

By

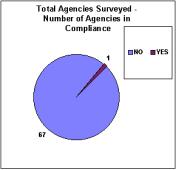

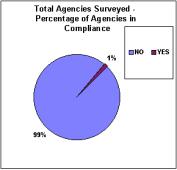

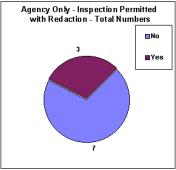

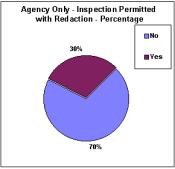

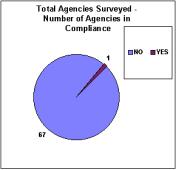

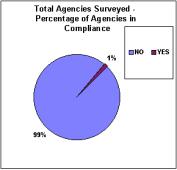

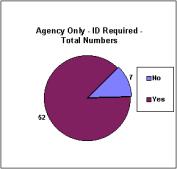

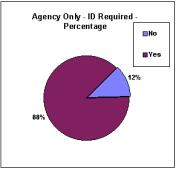

any standard, the performance of state agencies was terrible. Only one of 68 agencies surveyed passed the

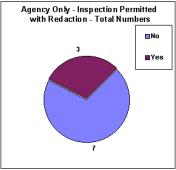

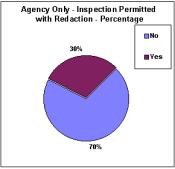

test (see Graph 3) and only 10 in total even allowed the

__________

*The Department of Public Health, the Elections

Enforcement Commission and the Ethics Commission were also in compliance in all

respects under their control, but either security personnel or personnel from

other agencies did not meet all of the established standards for compliance.

surveyor to inspect the requested record. In the 1999 survey of local government, 22

percent of the offices surveyed were in

compliance with the statute. That

included 10 percent compliance by school districts, a 21 percent rate by

police, and 37 percent from town clerks.

Although this was a dismal performance, it shines when compared with the

compliance rate of state agencies, which works out to a worse than meager 1

percent (see graph 4); even when the more liberal standard of eventual access

is considered as the benchmark, the success rate is still only 15 percent. See Graph 2, page 9 above.

Graph 3 Graph 4

The

survey sets the bar high, but no higher than the law requires. But there may be a significant gap between strict

compliance with the law and ultimate access to records. In the case of state agencies there were not

one but two hurdles for surveyors to overcome.

What tripped up almost all agencies was an identification requirement

just to satisfy building security. As a

matter of fact, a number of surveyors never got any further than the lobby of

the building in which the agency they were assigned to survey was located. Some were told over the phone that they

could not see the records, but others dealt directly with individual staff

members who came down to the lobby to find out more about what they

wanted. However, being quizzed in a

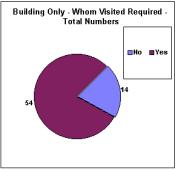

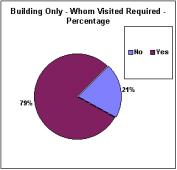

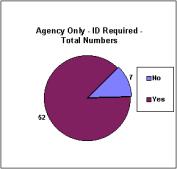

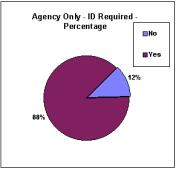

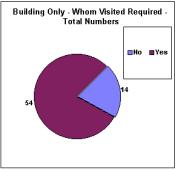

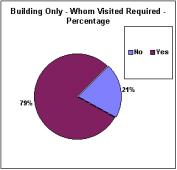

building lobby did not lead to access to the records in any cases. Graphs 5-10 show respectively the number and

percentage in which building access was granted and denied on condition of

providing name, when visited and personal identification.

Graph 5 Graph 6

Graph 7 Graph 8

Graph 9 Graph 10

In

those rare cases when a surveyor got to an office past security, or where there

was no security, those individuals at the agencies who helped the surveyors

frequently asked the same questions who are you, where are you from, why do

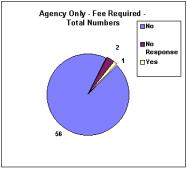

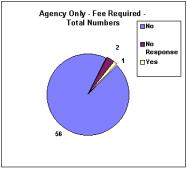

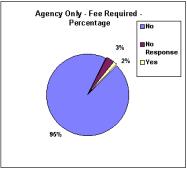

you want to see the attendance record for the head of the agency? See Graphs 11-16, which illustrate some of

the barriers imposed on the surveyors.

The law clearly provides that such questions are irrelevant to rights of

access and implicit in such questions is an unwelcome potential for

intimidation.

Graph 11 Graph 12

Graph 13 Graph 14

Graph 15 Graph 16

But

at only 10 agencies did the staff conclude that the records were public and that

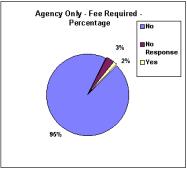

they were required to allow the surveyor to view them. See Graphs 17 and 18. Personnel at a number of agencies believed

the records were either confidential or private. See Graphs 19 and 20, page 13 below. At others, surveyors were told that they must submit a written

request. See Graphs 21 and 22. Some even indicated that the surveyor would

have to make a request to the FOI Commission in order to gain access to the

records. Others were under the

impression that attendance records were personnel records and that access to

them was dependent on the consent of the individual the records were

about. Finally, a handful of agencies

the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Treasurer, Attorney General, and others

told requesters that the heads of their agencies were constitutional officers

on set salary and that no record was kept of their attendance at work.

Graph 17 Graph 18

Graph 19 Graph 20

Graph 21 Graph 22

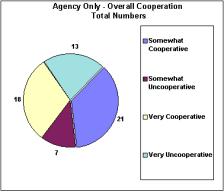

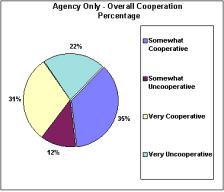

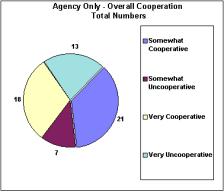

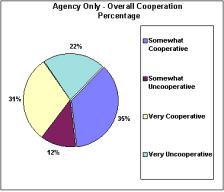

Surveyors

were asked to rate the agencies in terms of how cooperative they were. This characterization was made separately

from whether or not the surveyors received permission to view the records and

was done to rate the customer service provided by each agency. The ratings started with a possible low of

Very Uncooperative, moved through the middle ground of Somewhat

Uncooperative and on to Somewhat Cooperative and finished with the highest

possible rating, Very Cooperative.

The majority of agencies were given acceptable scores, with 18 agencies

rated as Very Cooperative and 21 agencies ranked as Somewhat

Cooperative. That left 13 agencies at

the bottom with Very Uncooperative and seven more with Somewhat

Uncooperative. So, approximately

two-thirds of all agencies were considered cooperative, but there is no reason

why 13 should have left such a bad impression on the surveyor that he or she

awarded them a Very Uncooperative.

See Graphs 23 and 24.

Graph 23 Graph 24

The

survey served to show just how far removed higher levels of government are from

the average citizen. Although the

compliance rate in the 1999 local government survey was not very good, most of

those individuals deal with people walking in off the street as part of their

regular work day. While many local

government staffers do not encounter the public on a daily basis, it is

considerably more likely for the average citizen to visit his or her town hall,

police station, or school district. It

is considerably less likely for the average citizen to visit a state agency

even if they live in the state capital.

As the chance of a direct face-to-face encounter with a citizen walking

off the street becomes more remote, such an occurrence engenders greater

surprise and suspicion on the part of the employee. While the surveyors were within their legal rights to come to the

agencies and request records, the rarity of such an event left many employees

scratching their heads, staring dumbfound at the requesters, and peppering them

with questions, more suspicious about why they were in their building than they

were interested in trying to help fulfill the surveyors request.

A

major part of the surveys construction was designed to test how agencies would

react to individuals coming in off the street.

The statute speaks both in terms of receiving a written response to a

request or inspecting documents onsite.

For the survey to be successful agencies needed to be canvassed quickly

so that word of the survey would not leak to other agencies and color their

performance. It also needed consistent

standards that might be harder to achieve if the agencies were sent requests by

mail. In other words, if a surveyor

visited an agency, he or she would either gain access to the records during

that visit or access would be denied.

Either way, the agencys compliance was completely tested by the end of

the visit. A written request would have

to rely on vagaries of mail delivery, intra-agency routing processes, and internal

policies that might require too many variables to properly quantify over a

short period of time. Even so, many

agencies believed a written request was the only way in which an individual

could gain access to records. See

Graphs 21 and 22, page 13 above.

A

number of agencies clearly had no clue concerning the public availability of

the records. At the Comptrollers

office the surveyor was told that they were not at liberty to just give out

that information and that the requesters general interest in seeing the

records was not a sufficient enough reason to allow inspection. After working their way to the payroll

office at the State Library, the surveyors were told that the information was

only available pursuant to a written request and even then the Librarian would

have the right to withhold his permission.

The head of the Properties Review Board actually allowed the surveyor to

view the previous months attendance records, but the surveyor noted that his secretary

kept trying to convince him that it was his personal business and he shouldnt

show us. At Naugatuck Valley

Community-Technical College, the presidents executive secretary was very brief

and told the surveyor she could not see the information unless she wrote a

letter to the president explaining why she needed the information and he was

willing to let her view it. At the

Department of Motor Vehicles in Waterbury, a security guard opined that the

records were not public. A woman from

public relations came down to speak to the surveyor and insisted that it was

absolutely necessary for her to provide her name, telephone number, school and

class. The surveyor at the Department

of Liquor Control was interrupted by a fairly rude man who kept asking her

who she was, where she came from and why she wanted to see the administrators

records.

But,

by the same token, some offices, while not allowing onsite review, clearly

tried to be responsive to the requester.

At the Department of Public Utility Control, the requester left her name

and phone number with the executive secretary.

The following week she received four phone messages from the FOI officer

at the agency asking the requester to call back because she was unclear about

what records the requester wanted to see.

Some

of the experiences of surveyors were so far out of line that they deserve a

closer recounting. The worst

experiences were as a result of running into James Papillo, the Victim

Advocate, who roamed the corridors of his building, accused several of the

surveyors of lying and actually grabbed one of them and detained her

momentarily. In their descriptions of

their encounters with Papillo, he comes off sounding more like a self-appointed

vigilante making sure the building is free from the prying eyes of citizens

than like a public employee whose job is to serve rather than harass

citizens.

Perhaps

the best way to feel the impact of Papillos shoot now, ask questions later

tactics is to quote at length the description of the female surveyor who had

the most direct confrontation with him.

Some of the small agencies the surveyors visited were located in the

same buildings, as was the case here.

I arrived at 505 Hudson around 12:30 pm. . .with my classmate and

walked up to the security desk. I told

the security officer that I needed to go to the Office of the Victim Advocate

and the Psychiatric Security Board office.

He proceeded to tell me to sign in and gave me a visitors pass that

said DCF [the Department of Children and Families, also located at 505 Hudson

Street]. He then told me that it was on

the 5th or 6th floor and to go on up. My classmate and I went to the 6th

floor first and realized it was not there, so we headed down to the 5th

floor. We found the Office of the Victim

Advocate but no one was there so we went to the office next door and asked

where they were. A lady nicely told us

that they were either out to lunch or just on a break. She also asked what we were doing and we

told her that we needed to see an attendance record for a school project. We then proceeded to Room 101 where the

Psychiatric Security Board was located.

We walked into the office and no one was at the receptionist desk. We said hello, a few times and no one

answered but we heard voices coming from the back, so we walked down and asked

if someone could help us. After being

told the director was not in, the two surveyors left the office. We left the office and went back up to the

5th floor to see if anyone was in the other office yet. Nobody was there so we went back to the

security desk and told them we had just come from the Office of the Victim

Advocate and nobody was there and asked if they were out to lunch or gone for

the day. They said that they were out

to lunch and that we should try back later.

We

returned a few hours later and my friend had decided to stay in the car, so I

had left my purse in there and went inside.

I walked up to the security desk and told them that I had been there

before and I needed to go to the Office of the Victim Advocate. The guard then pulled out the logbook and

pointed to my name and asked if that was my name. I noticed that my name had an arrow next to it. I said yes and he asked me who I needed to

speak to there and I told him that I just needed to see a secretary or the

human resources person. He then asked

what I needed and I told him that I needed to see the attendance records of

James F. Papillo. He then went

upstairs. After some back and forth

with the guard, the surveyor was told that someone would come down to talk with

her shortly.

A

man came down and approached her, apparently to shake her hand. But it was not the normal way a person

would shake hands. He squeezed my hand (it

was almost as if he wanted to intimidate me or let me know that he was the one

in control). He did not introduce

himself to me, he just asked what I wanted and I said that I needed to see the

attendance records of James Papillo. He

then asked for ID and I told him that I had left it in the car and asked if he

wanted to go get it and he said yes.

So I went outside and ran around the corner to my car that had been

parked on the side of the building. . .I then proceeded to walk up to him and

showed him my school ID and my license.

He inspected them and handed them back.

Then he asked me what I needed to see the records for and he asked me

what type of class and professor it was for and I told him it was for

psychology class. At that point he

grabbed my arm and told me that I was full of shit and that we were going

inside and he was going to call the police.

I then pulled my arm away and asked him what he was talking about. He said that he already had a call into my

professor and wanted to know what kind of scam I was running. I told him again that I was doing a school

project and it seemed as if he did not believe me and that is when I said that

we were not supposed to say that we were journalism students. [It was decided in setting up the survey

that mentioning that they were journalism students could affect the behavior of

agency employees because there is some evidence that government employees

provide greater access to records to the press as opposed to the average

citizen.]

He kept asking why

we werent supposed to say that and I kept telling him that I didnt know. He continued to go on how I had caused a

breach in security earlier. . . What kind of project was it? Were we just trying to get peoples

reactions when asked for these records because we couldnt just walk in and get

this type of information. He motioned

to me by moving his hand up and down and said that a person could not just walk

in off the street and see them. There

were proper channels and procedures that I needed to follow and the teacher

should have called beforehand and arranged it unless he wanted us to learn that

this was not the way to go about getting this type of information. My teacher was wrong to send us out there. He would need time to check if this was public

information and if it was, if the FOI required a written request. I then said that I was under the impression

that I did not need to give my name or why I wanted it and he said that that

was wrong.

As

if dressing down a citizen for no apparent reason and gleefully exhibiting his

total ignorance of the law wasnt enough for one day, Papillo continued his

rampage with yet another student surveyor who had the ill luck to enter the

building just as the first surveyor was leaving. This surveyor intended to canvass the Board of Firearms Permit

Examiners, but met Papillo in the lobby instead. She noted that the man was very nasty. He said to the security guard that no one is to roam the

halls. He said we were liars, lying

about who our professor is. The guard,

who had already been criticized by Papillo, refused to allow the new surveyor

to go into the building, insisted she call up the offices and told her she

would be thrown out of the building if she continued to persist in her quest to

see the records.

If

this is the caliber of employee hired by Connecticut, the state has some

serious personnel problems. But

Papillos brutish behavior might be excused as that of a mad dog if it werent

for the fact that some of the same kind of paranoia was displayed at other

agencies. A male surveyor got something

of the same treatment at the Department of Veterans Affairs. After having a pleasant but fruitless

conversation with several people in the payroll office about viewing the

records, the surveyor was stopped in the hallway by the director of

security. The director asked why he was

there and then asked for his ID, writing down the information. He then escorted him out of the building at

which time he asked him how he had gotten into the property in the first

place. The surveyor explained that he

had pulled up at the guard gate and been waved in without any problem. The director had the surveyor go to the

guardhouse with him. He asked the guard

if he remembered seeing the surveyor and the guard said no. The director then had him sign in and

watched him until he had driven out of sight.

Another

surveyor found that her visit to the Military Department unexpectedly came back

to haunt her when she was interviewing for an internship in Congresswoman Rosa

DeLauros office. Her interviewer told

her that someone from the Military Department had contacted him and said the

surveyor had indicated to his staff that she was already interning at the

Congresswomans office. Explaining her

actions in a later letter of complaint, the surveyor indicated that while I

was at the Military Department waiting for the record, his assistants were

asking me what my plans were for the summer they were just trying to make

conversation and I had mentioned that I was planning to intern at Rosa

DeLauros office. I did not say that I

was already interning. She added that

I was very intimidated when [the interviewer] interrogated me about why I had

told the Military Department that I was already an intern at his office. Also, there should not be any reason for

[the General] to check up on me.

For

participants in a survey to test agency compliance with an open government

obligation to find themselves under suspicion for trying to view public records

is upsetting to say the least. While

these experiences were limited, they were totally uncalled for and suggest that

those government employees involved perhaps need to spend some time learning

the basics about open democracy.

Building Security

vs. Open Government

What happens when the mania for

security runs into conflict with open government? Unfortunately, open government loses. The FOI Act provides the right to inspect public records onsite

at an agencys office. But that right

is hollow if the requester is not allowed to go to the agencys office. A number of building security guards did not

consider the statutory rights provided by the FOI Act to be an adequate reason

to gain admission to a public building.

In

survey sheets for 16 different agencies, some of which were located in the same

building, surveyors reported that they either were not allowed any further than

the building lobby, or, in one case, were not allowed into the building at

all. In three cases the Department of

Economic and Community Development, the Department of Information Technology,

and the Department of Transportation the surveyors reported that it was the

security guard who would not allow them to go any further, in at least one

instance the guard made the tentative ruling that the records were not

public. In a criminal justice agency

the Board of Parole the surveyor was not even allowed into the building. At the Board of Parole, a security guard at

the front door called upstairs and a woman came down and talked with the

surveyor through the door. Once the

woman went back upstairs, the surveyor waited until she called down to the

security guard that the records were not public.

In

other agencies, the surveyors made it as far as the lobby, but no further. Instead, someone came down and told the

surveyor that he or she could not see the records. Such agencies included the Attorney General, the Board of

Firearms Permit Examiners, the Board of Labor Relations, the Building

Inspector, the Comptroller, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of

Motor Vehicles, the Department of Public Safety, the Department of Revenue

Services, the Department of Social Services, the Division of Criminal Justice,

and the Treasurer.

The

concern for building security is understandable and was probably heightened by

the Oklahoma City bombing and the shootings at the State Lottery. [Note that this survey was conducted before

the tragic acts of terrorism on September 11, 2001.] But security comes with a price for access. And when it comes to asserting rights to

view public records at the agencys office, the right is useless if the

requester is not allowed to visit the office.

Almost all security guards asked where the surveyor was going and who he

or she was. Where controlled entry and

exit are deemed necessary, that kind of gate-keeping operation is probably

necessary. But it does not necessarily

follow that a citizen with a legitimate reason for entering the building should

be denied access to a government agency and told to wait at the tradesmens

entrance instead until the residents of the building come to answer the door.

Government

must find some way to reconcile these competing interests that preserve the

essential needs of both. Although we

would like to think our government is open and accessible, that goal probably

cannot be fulfilled when faced with legitimate security concerns that prohibit

the ability of citizens to freely roam the corridors of government. Even so, as long as a security guard knows

that someone is in the building and where they are going, that would seem

sufficient in virtually every instance.

Surveyors who visited the offices of the Governor and the Lieutenant

Governor in the Capitol Building commented on how open the building was

compared to any other state building visited.

Of course, such legislative buildings have a long history of being open

and dealing with public comings and goings and have grown substantially more

comfortable with such movement. Only

time will tell whether this tradition will continue after the events of

September 11th.

Integrity of

Government

Democratic

government is based on the consent of the governed. That consent is based in large part on the public understanding

that the people who make up its government perform their jobs competently and

diligently and act reasonably and responsibly in carrying out their

functions. One of the most important

functions is to obey the law and it goes without saying that the public should

be able to anticipate that its legal rights will be recognized, not ignored.

Because

of the insularity of government as it becomes more removed from daily

interaction with the public, to send citizens into government agencies who may

realistically never deal with individuals off the street provided a challenging

test to the ability of those agencies and their employees to recognize their

statutory obligations and fulfill them.

Based on the results of the survey, the government as a whole flunked

with flying colors. But its inability

to process a walk-in request for a standard public record carried an impact

greater than just passing or failing a test.

It also provided many of the surveyors with personal illustrations of

how poorly government operates, how an encounter with a government employee can

prove to be intimidating, unpleasant, and sometimes downright nasty.

The

surveyors reports are full of reflections of the individual surveyors that

convey a consistent disenchantment with government and perhaps a certain sorrow

that citizen interactions with government can be so frequently

disappointing. One surveyor observed

that the overall feeling I received after doing this survey experience is

intimidation. It was not so much that

the people themselves were intimidating, while in some instances that was the case,

but the process of going to these buildings and getting to the different

government offices that caused my feelings of intimidation. Another noted that I did get the feeling

that the information I was requesting was top secret and that my request was

unusual. At some points I did get the

impression that I had no business with the information that I was requesting to

see. Had I been just a regular citizen

coming into either office and had not known my rights, I would have been more

than a little intimidated. Even knowing

that I was perfectly within my rights asking for this information, I did at

times feel a little intimidated.

Another surveyor said that at first, I really didnt want to do this

assignment, but at the end I found this to be a very eye-opening

experience. Perhaps the results will

turn into public embarrassment for those agencies involved, but I also think

there should be some other kind of punishment, such as fines, in order for this

problem to be fixed at least a little.

Another added that the amount of agencies that denied access to these

public records is unbelievable.

Hopefully the work we did will demonstrate the amount of agencies not

complying with the laws, or not having a solid understanding of what the law

is. I pity any citizen who requests

these records and is not one hundred percent sure of their rights, because the

response is brutal. Finally, a

surveyor commented that after hearing the similar experiences my classmates

had, I realized what a problem we have on our hands without an easy solution in

sight. There is already a law to

protect citizens rights, but not every state agency follows the law.

One

surveyor explained that all I can really say about the FOI Commission survey

is that it left me feeling exceptionally jaded toward our state

government. I did not really expect

that very many offices would be in compliance, but I also did not expect the

level of paranoia that was encountered.

A week after his canvassing, he found that agency employees had

contacted his professor to verify the surveyors identity. He noted that at first I found it funny,

but now I think it is really just sad.

The whole incident just shows that not only is the government so afraid

of the public that it makes it nearly impossible to get certain records, but it

actually tracks and traces whom those people are. Perhaps if I had made a threat or had been in any way hostile or

ill-mannered, I could understand the follow-up, but this bordered on some sort

of Big Brother spy job.

One

surveyor had some comments about her treatment by security guards. In my own experience, I dont appreciate

being given the run around purposely when I stated my request numerous times. Security guards all over the city of

Hartford, at some particular state buildings, are trying to disinterest and

mislead the public. She added that

security guards and state workers all throughout Hartford and elsewhere in the

state need to be re-educated as to the laws before accusing private citizens of

being in the wrong. The legislature

should seriously look into the matter.

I have no problem informing my elected officials of the situation and

urging them to do something about it.

These

comments reflect experiences with state government that are guaranteed to be

off-putting at the very least. Such

paranoia and ill-mannered behavior does not engender trust in government; it

does the exact opposite. Perhaps these

students betray a certain naivetι about the real world, but if the real world

consists of officials who havent any idea what the law is and cant abide by

it as a result, then it may not be the kind of world into which these students

would choose to graduate.

At

least one surveyor was able to articulate an explanation for government

workers behavior. He noted that the

nature in which we confronted the various offices around the state made them

feel vulnerable. We didnt have an

affiliation, didnt have a purpose, didnt want to give our identity. This all adds up to a very shady appearance

on our part. This surveyor indicated

that he found agency staff to be cooperative, but pointed out that its only

natural when someone asks you for an outlandish request to ask why you

requested this information. Clearly

these offices were not briefed on FOI regulations and therefore resulted in

failure of the survey, but the nature of our request (attendance of the highest

ranking official) caused a likely reaction, they felt vulnerable. One womans

eyes and facial expression actually grew a look of fear and her actions became

hesitant. He concluded that all were

quite cooperative with me, they just didnt know what the FOI specs were, so

they were apprehensive about complying with this outlandish request.